Beam Bridge Models: Difference between revisions

From DT Online

m Added Category |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

*how deep was your beam? | *how deep was your beam? | ||

*what types of traffic or services could pass over your beam? | *what types of traffic or services could pass over your beam? | ||

. . . or even through your beam . . . the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Britannia_Bridge '''Britannia Bridge'''] across the '''Menai Strait''' was originally designed and built by [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Stephenson '''Robert Stephenson'''] as a tubular bridge of [ | . . . or even through your beam . . . the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Britannia_Bridge '''Britannia Bridge'''] across the '''Menai Strait''' was originally designed and built by [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Stephenson '''Robert Stephenson'''] as a tubular bridge of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wrought_iron '''Wrought Iron'''] rectangular box-sections for carrying rail traffic inside - but it had to be rebuilt following a fire in 1970. | ||

[[File:LoadedBeams2.png|800px|bottom]] | [[File:LoadedBeams2.png|800px|bottom]] | ||

Revision as of 10:13, 1 March 2017

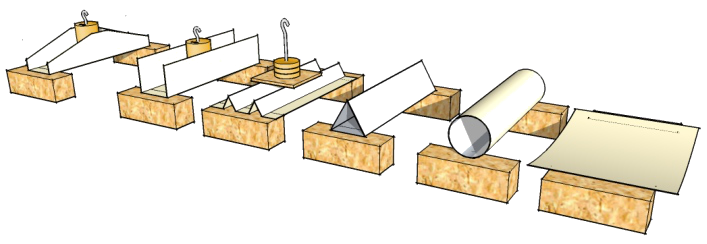

The effectiveness of a material for bridge building depends on the way it is used. Paper or thin card might not appear to be able to support much load but it is possible to greatly increase its strength by manipulating its shape.

Description

Place two wooden blocks or similar supports 250mm apart then design a beam bridge to span the gap between them using A4 paper or thin card. Try different designs and test each one by loading it until it fails.

You can either add small weights to the top centre of the beam or suspend a paper cup or similar underneath and slowly fill with sand. In either case you may wish to place a small section (say, 50mm square) of thicker card in the centre of the beam to spread the load a little.

Testing

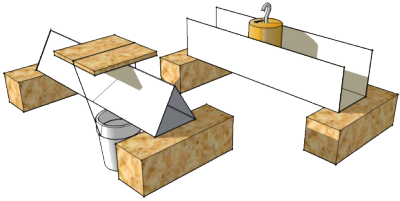

Make a sketch of each design and record the results:

- how much load did it take?

- how wide was your beam?

- how deep was your beam?

- what types of traffic or services could pass over your beam?

. . . or even through your beam . . . the Britannia Bridge across the Menai Strait was originally designed and built by Robert Stephenson as a tubular bridge of Wrought Iron rectangular box-sections for carrying rail traffic inside - but it had to be rebuilt following a fire in 1970.

- were some shapes stronger than others?

- was it the widest beams that were strongest or the deepest?

Modern Steel Beams

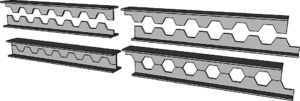

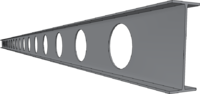

You will notice a difference if you try bending a ruler first on its side and then on edge. The steel girders or joists seen in building construction are often made in an 'I' section which is taller than it is wide. The narrow 'flanges' at top and bottom are there mainly to stop the beam buckling and twisting under load - and to provide a flat supporting surface.

Lightweight steel joists have holes along the centre, or Neutral Axis, of the vertical web. You may also see these used in the chassis of trucks for example.

In a Castellated Beam, these are created by cutting a standard RSJ, separating the pieces to re-align, then welding back together along the Neutral Axis.

This produces a lightweight beam and also increases the depth. All holes are along the centre of the web where there is least stress and the weld is along the Neutral Axis, where there is little or no stress.

A Cellular Beam is the modern version of the traditional "'castellated'" beam and results in a beam approximately 40–60% deeper than the original RSJ.

Note: If beams or joists have to be drilled to accept pipes or wiring etc., it is best to pass them close to the Neutral Axis to avoiding weakening the beam. (For convenience, notches are often cut into the top surface of a floor joist to receive wires or domestic plumbing. This is usually acceptable providing they are small because the top is in Compression and this will tend to close them up. Notches cut into the bottom of joists should be avoided since this would create a potential fracture point as a result of the Tensile Forces pulling it apart).

Traditional Timber Beams

In contrast to modern practice, if you look inside a Medieval timber-framed house, such as the Merchant Adventurers' Hall in York for example, you will notice that roof and floor beams are often wider than they are deep.

This arises from the need to make things out of logs and tree trunks, without modern high-tech saws to cut sections from the starting material stock. A freshly felled 'green' log is 'cleaved' down its centre using axes and wedges. The resulting half-round section is squared off using axes, adzes and draw knives but the original central 'cleaved' surface provides a good flat surface on which to fix roofs and floors.

The result is a very heavy and over-sized beam - but trees at that time were plentiful!